20 Nov The cyber threat environment today: an ‘asymmetric warfare’

Author: Helaine Leggat

Last month our Australian article began with a quotation from the Hon Clare O’Neil MP, Minister for Home Affairs and Minister for Cyber Security, who said “Directors have a critical role to play and must seek to uplift their own cyber literacy levels, recognising that this is a key risk that can never be eliminated but can be effectively managed.”

This article will look at what is involved in uplifting cyber literacy levels, and at the context in which cyber literacy fits.

Interestingly, the Minister’s statement which followed several significant cybersecurity breaches coincides with the announcement that Dr Tobias Feakin, Australia’s first Cyber Ambassador is stepping down from the role after nearly six years with the federal government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT).

The relationship between Australia’s recent cyber breaches and that of Medibank in particular, where the alleged attackers are believed by experts to be linked to Russia-backed cybercrime gang REvil, is an important part of understanding the context and scale of what needs to be done. The fact is that a criminal gang, nation state or nation state proxy is now commonly an adversary of private sector organisations and the individuals whose personal information comprise the ‘crown jewels’ of organisational assets.

Understanding how this came about is key to understanding how to approach an uplift in cyber literacy.

Pre-Internet legal order: Horizontal and vertical relationships

Under the pre-internet system of global norms there was a respected system of legal order adhered to by sovereign states in which they recognised each other in horizontal relationships as ‘equals’. Coexisting with these international relationships, each sovereign state had power and authority over its physical jurisdiction and its peoples (individuals) and juristic persons (corporate entities). These were vertical relationship with power vested in the state. Each sovereign state was responsible for the national security of its geographical jurisdiction and its peoples and corporate entities. It was the state’s function to maintain law and order in both these horizontal and vertical relationships.

Sovereign states frequently maintained peace and order in international relationships between one another through international conventions (treaties) negotiated through the executive branch of government like DFAT in Australia. The terms of conventions were in turn adopted into the national laws of sovereign states as signatories to a convention, meaning that each state could enforce its international obligations upon its own corporate entities and individuals.[1]

Enforcement of the horizontal international relationships was the domain of national defence. Enforcement of the vertical national relationships was the domain of law enforcement. Failed international relationships between states could result in war, sanctions and trade embargos etc. Failed domestic relationships could result in imprisonment, fines, enforcement orders, civil wrongs etc. While this summary is hugely simplified, it is useful in understanding the breakdown of legal order brought about by the internet.

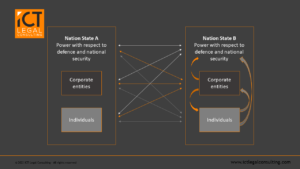

Generally, this system of international norms of behaviour worked, and each state was responsible for the norms of behaviour agreed to with other states, including enforcing the behaviours agreed to internationally upon its own corporate entities and individuals. The diagram below shows the structure of horizontal and vertical order and power.

Figure 1: The Pre-internet Legal Order

Figure 1 shows the horizontal relationship between sovereign states: Australia (left) and other state (right) where horizontal sovereign power is recognised under international law; and the vertical power of the state over corporate entities and individuals enumerated under the Legislative Powers of Parliament in Section 51 of the Australian Constitution. This hierarchy is mirrored in other nation states.

Post-Internet legal disorder: Asymmetric and dynamic

The system described above no longer functions as a system of norms of behaviour. In cyberspace the old system of legally recognised vertical and horizontal relationships has broken down.

Individuals and corporate entities, acting on their own behalf or as proxies for others, including as proxies for nation states, usurp the sovereign power of a state and attack other sovereign states. Sovereign states disregard the old system of norms and use cyber weapons to engage in attacks against the critical infrastructure of other sovereign states. Sovereign states, individuals, and corporate entities actively purchase exploits for use against sovereign states, individuals, and corporate entities. Corporate entities engage offensive actions that have traditionally been the reserve of state power.

Figure 2: Post-Internet Legal Disorder

Figure 2 shows how individuals and corporate entities appropriate the power of a nation state in a new form of non-geographic threat-attack behaviour that has broken down the previous order of horizontal and vertical legal structures.

What does this mean?

It means that sovereign state powers and functions historically deployed abroad need to be deployed abroad, and also, at home. It means state powers and functions are locally deployed as envisaged under the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 (Cth) (SOCI), and it is not sustainable in the long term for national resources intended to be deployed internationally to be deployed internally as well, and at scale.

The internet, ubiquitous availability of computing devices and reduced levels of attribution have led to an increase in crime that means states are simply not able to provide security to all of their corporate entities and individuals, nor, to secure and defend national critical infrastructure (or other businesses) all of the time and against all of the new attacks and attackers. It means that corporate entities and individuals need to take responsibility to secure themselves and their communities.

Practically, this means that an organisation like Medibank must harden its environment to withstand an attack from Russia and its acolytes.

The increase in frequency of cyberattacks also means there is a significant increase in the ramifications of not undertaking appropriate due diligence (identifying risk) and acting with due care (doing something about the risk identified). It means that the stakes to business are incredibly high, and directors are vulnerable to external (cybercrime) and internal risk (shareholder actions), to say nothing of reputational harm, financial loss and the like.

Australian Government actions

The Australian Government is taking extraordinary steps, including that the Minister for Home Affairs and Minister for Cyber Security, and Attorney-General, recently announced that the Australian Federal Police and the Australian Signals Directorate will initiate an ongoing, joint standing operation to investigate, target and disrupt cyber-criminal syndicates with a priority on ransomware threat groups. This operation will collect intelligence and identify the ring-leaders, networks and infrastructure to disrupt and stop their operations – regardless of where they are in the world. However, it does not mean that directors can leave security to government, as the $750,000 fine imposed on RI Advice[2] has shown.

Cyber uplift for to today’s asymmetric warfare conditions

The cyber threat environment today is akin to ‘asymmetric warfare’ – the term given to describe a type of war between belligerents whose relative military power, strategy or tactics differ significantly. Asymmetric warfare is typically a war between a standing, professional army and an insurgency or resistance movement militias who often have status of unlawful combatants.

Translating this to the cybersphere means states, state proxies, criminal gangs vs. corporate entities and individuals, and this demands a new strategy intended to gain intelligence and engage attackers.

Active Cyber Defence

Active cyber defence is a term that captures a spectrum of proactive cyber security measures that fall between traditional passive defence and offense. These activities fall into two general categories:

-

-

- the first covering technical interactions between a defender and an attacker; and

- the second includes operations that enable defenders to collect intelligence on threat actors and indicators on the internet.

-

The term active cyber defence is not synonymous with ‘hacking back’ (unauthorised access), and the two should not be used interchangeably. Offensive cyber actions are the sole domain of authorised government agencies.

Take aways

In order to uplift your cyber literacy levels and effectively manage cyber risk, you will need to start planning and discussing adversary engagement operations that empower you to engage your adversaries.

Unlike many other defensive technologies, the active cyber defence technologies which include cyber deception, are not ‘fire and forget.’ Rather, deception technologies should be deployed as part of an intentional strategy that drives toward well understood goals.

Here to help

Our team of lawyers and cyber security experts have decades of experience in active cyber defence. Please contact us if you’d like to develop a strategy or simply learn more.

[1] The Cybercrime Convention and the Australian Criminal Code are examples how unauthorised access became Australian law.

[2] Australian Securities and Investments Commission v RI Advice Group Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 496.